There are three churches especially associated with Doagh. Only one of them is in the village itself – Doagh Methodist Church. The other two – Kilbride Presbyterian Church and Kilbride Church of Ireland – are located outside the village, but are still inextricably linked to it.

Doagh Methodist Church

In 1738 John Wesley and his brother Charles started the movement that soon acquired the name of Methodism. John Wesley made his first visit to Ulster, where the movement had already established itself in many of the major towns, in 1756. He visited Ulster regularly for the rest of his life. By 1778 a Methodist Society had been established in Doagh.

It seems likely that John Wesley himself visited Doagh in that year. He recorded in his journal that while travelling between Ballymena and Carrickfergus in June 1778, ‘We rode through a small village wherein was a little Society. One desiring me to step into a house there, it was filled presently, and the poor people were all ears while I gave short exhortation and spent a few minutes in prayer.’ Though Wesley does not state that this incident occurred in Doagh, this would have been the village he most likely passed through on his way to Carrickfergus.

In 1799 the Methodist Conference gave its sanction to the building of a meeting house where the present building now stands. In the same year a young man arrived in Ireland from America. His name was Lorenzo Dow and he was a candidate for the Methodist ministry in America.

On coming to Doagh he was initially opposed by the officer of the guard, but on the Sunday the military parade was cancelled so that the soldiers would have the opportunity to hear him. He preached to the soldiers in the out-houses of Fisherwick House.

In the late 1830s the Methodist meeting house in Doagh was described as a single-storey building with a slated roof, but ‘in bad repair’. Externally it measured 21 feet by 18 feet with 2 small oblong windows and a door. Meetings were held in it every Sunday morning and every Tuesday evening. There was regular preaching in it once a fortnight conducted by a Methodist ministers, but the other meetings were taken by laymen.37 At this time there were about 70 members.

In 1844 a new Methodist meeting house was built in Doagh on the same site as its predecessor. The date-stone reads:

Wesleyan

Methodist Chapel

Holiness becometh

thine house, O Lord,

for ever

1844

Kilbride Presbyterian Church38

Around 1840 the Carrickfergus Presbytery became aware that Presbyterians living in Kilbride were willing to be formed into a congregation. At this time Presbyterians from the Kilbride-Doagh neighbourhoods belonged to the Presbyterian churches of Donegore, Ballyclare and Ballyeaston.

The Presbytery authorised a series of meetings in Doagh, but the response to these was disappointing with very small attendances. The matter was held in abeyance for a number of years.

At the end of August 1844, the Carrickfergus Presbytery encouraged congregations to establish prayer meetings in areas where they had not previously existed. It seems that meetings for prayer were established at Brookfield at this time. According to oral tradition, these meetings were held in the loft of a weaving shed close to Brookfield House, then the home of James Watt who had purchased Springvale Weaving Mill.

It seems that one of the early encouragers of the Brookfield meetings was Thomas Lyle, the manager of the Springvale Weaving Mill, who would later become one of the first trustees of the property of Kilbride Presbyterian Church. Rev. William Raphael of First Ballyeaston was also heavily involved in what became a recognised missionary station.

In February 1846 Mr Raphael informed the Carrickfergus Presbytery that those who gathered for services in Brookfield were anxious to become a congregation in their own right. He had already secured the approval of the Home Mission in having a young man placed in this area to provide regular preaching. In May Mr Alexander Barklie, the son of James Barklie who farmed at Ballynure and Rashee and was related to the Barklies of Kilbride, was appointed to preach at Brookfield and his initial experiences were very positive. By this time serves were being held in the schoolhouse adjoining Kilbride graveyard.

Following a meeting in October 1846 it was agreed to continue with Mr Barklie’s services for another six months and to immediately establish a congregational committee. Henceforth the embryonic congregation was known as Kilbride, not Brookfield. Barklie also conducted services in Doagh every other Sunday evening; the venue may have been a building known in former times as ‘The Tabernacle’, to the rear of the Torrens Memorial Hall.

On 4 November 1847 a memorial signed by 120 heads of families was presented to the Carrickfergus Presbytery requesting they be erected into a congregation. The request was granted. Back in July of that year William Orr, a licentiate of the Dungannon Presbytery, had been appointed to have oversight to the missionary station here. He was ordained minister of the new congregation on 14 March 1848.

A plot of ground adjoining the schoolhouse and old graveyard having been secured from Robert McClelland, a meeting house was built under the direction of William Lawson, who had been born in Kilbride, and later moved to Ballyclare. The meeting house was opened on 13 March 1849. The first five trustees of the church property were Thomas Lyle of Brookfield, Thomas Wilson of Drumadarragh, Charles Bryson of Ballybracken, John McClelland of Ballyvoy, and William Lawson of Ballyclare.

Kilbride Church of Ireland

For over 250 years, from the early seventeenth century to 1864, Kilbride and Donegore were united parishes within the Church of Ireland. During this time there was never a church in use in Kilbride parish, the old pre-Reformation church having been allowed to fall into ruin.

A nineteenth-century act of parliament provided a basis for a restructuring of the parish network within the Church of Ireland and, with specific reference to this area, for the separation of Donegore and Kilbride. However, this would not take place until the death of the existing incumbent, Rev. George Henry McDowell Johnston.

Rev. Johnston was the son of William Johnston of Ballywillwill, County Down, and his wife Rebecca, daughter of Rev. George Vaughan, rector of Dromore, also County Down.

Educated at Trinity College, Dublin, he became vicar of Donegore and Kilbride in 1814 and rector of those parishes in 1831. He married his cousin, Lady Anne Maria Annesley in 1811. Rev. Johnston acquired a house at Ballyhamage as his residence in the parish, though he seems to have lived at his mansion at Ballywillwill a great deal of the time.

In the Ordnance Survey memoir of the parish from the late 1830s, it is observed that Rev. Johnston ‘comes here merely on Saturday, attends church on Sunday and departs to his residence in the county Down on Monday.’39 It is said that on those Sundays he preached at Donegore he would transport some of his parishioners from Kilbride across to the church there in his carriage. Those whom he transported over had to walk back, while those who walked over were given a ride in his carriage. In the early 1830s some provision was made for the Anglicans of Kilbride for in 1832 it was reported that the rector had recently begun holding services in the schoolhouse beside Kilbride graveyard.40

By the early 1850s Rev. Johnston had built an extension to his home at Ballyhamage which he intended to use as a church for Kilbride. He did not reveal his plans to Richard Mant, Bishop of Connor, hoping that it would a pleasant surprise for him when he was invited to consecrate however. The Bishop, however, was rather annoyed with Rev. Johnston for not consulting him about this beforehand.

He was also rather concerned when he learned that the intended church abutted Johnston’s home, which was the rector’s private property, and that a door connected the two. Reportedly furious with Rev. Johnston, Bishop Mant refused to consecrate the church, but was willing to licence it for public worship.41 Thus, it became a kind of chapel of ease and is marked on the Ordnance Survey map as such. Rev. Johnston held regular services in it until his death on 22 May 1864. He was clearly a wealthy man for at his death his estate was valued at just under £4,000.

With Rev. Johnston’s passing Donegore and Kilbride were now formally separated. The new rector was Rev. Francis Charles Young, the previous rector’s nephew and heir. As Kilbride was now a charge in its own right, it was necessary for it to have a parish church. An elevated site in the townland of Ballyhamage, 20 yards south of its boundary with the townland of Kilbride, was secured from the Marquess of Donegall. The expense of building the church was met by a grant from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and through subscriptions raised by the rector. The new church was consecrated on 9 June 1868 as St Bride’s Church.

Doagh graveyard

Doagh graveyard is located on the south side of the village. Now in the care of Newtownabbey Borough Council, it was once the site of a medieval church known as the Church of St Mary of Doagh (Ecclesia Ste. Marie de Douach). By the early 1600s this church was in ruins. Only a portion of the west gable, standing to around 7 feet in height, still survives. Several mature trees stand at the east end of the graveyard, which is well maintained and in good order.

In 1839, James Boyle of the Ordnance Survey described the graveyard as follows:

The burial ground includes a quadrangular space of 109 by 133 feet, pretty well enclosed by a quickset fence with a small iron gate. The graves are very numerous, but are kept in rows without being crowded. Its surface is tolerably level and it is altogether rather decently kept. There are not any old tombs or headstones. No particular family, nor one of any note bury here. It is the usual place of interment for the people of the neighbourhood.42

Within the graveyard is a low-walled enclosure topped by metal railings marking the resting place of members of the Shaw family. The first name on the large gravestone within the enclosure is that of Edward Shaw who died in 1761 aged 86. His son William predeceased him, dying in 1759 aged 38. William’s son, James Blair Shaw, a linen draper in Doagh, died in 1818 aged 70. In his will of 1816, James Blair Shaw, probably the leading full time resident in the village at that time, requested to be interred in the ‘Family Burrying Ground’ in Doagh, with the following stipulation:

I order that a tombstone be purchased by my trustees and laid over my grave, raised on stone and lime, and also a wall built around the said family burying ground, also with lime and stone, all at the expense of my legatees.43

This graveyard is also the burying place of the Alexander family of Holestone. James Alexander died in 1887 aged 75. His son William (1845-1919) studied medicine at Queen’s College, Belfast, and went on to become a successful and highly respected surgeon in Liverpool, pioneering several innovations in operating procedures. In his retirement he moved to Heswall where he named his house Holestone.

There are several Hunter headstones, one of which commemorates Annie Elizabeth Hunter, wife of David Hunter, who died on 1 March 1898. There was a strange occurrence at her burial. It was found that the coffin was too large for the grave and so the gravedigger, John Gilmore, went in to enlarge it. Some of those standing by noticed that the sides of the grave were about to collapse and called out to Gilmore to warn him. However, before he could exit the grave he suddenly dropped dead.44

Kilbride graveyard

Situated on an elevated site overlooking the village of Doagh and with magnificent views along the Sixmilewater Valley, Kilbride graveyard has been a place of burial for centuries. Though Kilbride Presbyterian Church is located beside the old graveyard it has no connection with it other than the fact that families associated with this congregation would have buried here. The graveyard is in the care of Newtownabbey Borough Council.

No trace survives of the pre-reformation parish church – the ‘Church of St Bride (or Brigid)’ – that once stood here. In the Ordnance Survey Memoir of the parish of Kilbride, dating from the late 1830s, it is stated that the foundations of the church, which measured 68 feet by 30 feet, had recently been removed. The Memoir also noted that the ‘oldest tombstone bears the date of 1674. There are several others bearing dates from 1676 to 1699. The name of Smith is that on the oldest stones.’

By far, the most interesting feature in this graveyard – and surely one of the most remarkable in any Ulster graveyard – is the mausoleum erected in memory of the Stephenson family. It has been likened to the Taj Mahal and was possibly inspired by the Indian associations of one of those interred in it. It was built of Tardree stone in the late 1830s at a cost of £1,300, paid for by Dr Samuel Martin Stephenson. He was born at Straidballymorris, near Templepatrick, in 1742, the son of James Stephenson, a farmer, and his wife Margaret Martin. After completing his studies at Glasgow University, he was ordained minister of Greyabbey Presbyterian Church in 1774. While he was minister of Greyabbey he studied medicine and in 1785 left the congregation to become a full time doctor.

He died in 1833 aged 91 after a distinguished career in medicine. His son Samuel Martin Stephenson junior was Superintendent Surgeon of the Madras Presidency; he died in 1834 aged 50. The iron door of the mausoleum bears the legend, ‘Rowan, Doagh, 1837’. This refers to John Rowan who operated the forge in Doagh. Immediately on the east side of the Stephenson mausoleum is a row of four headstones commemorating members of the Galt family. One these was erected in memory of the famous William Galt who died in 1812 aged 61.

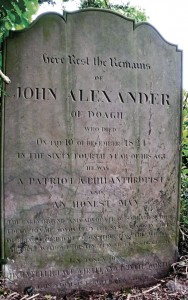

One of the most interesting inscriptions is found on the headstone to John Alexander of Doagh who died in 1824. to a remarkable inhabitant of Doagh in the early 1800s. The inscription tells us that he was ‘a patriot, a philanthropist and an honest man, the early friend and advocate of Sabbath School Education’. He was the John Alexander who had been gaoled for a time in 1796 and whose potato crop had been harvested by over 1,000 people who had gathered at Doagh to show their sympathy for him.

According to his obituary in The Rushlight, ‘possessing some comic powers, he at different times played the chief characters in several comedies acted in Doagh’.45 John Alexander was also well-known locally as a collector of ‘antiquities and other curiosities’.

Standing near the east wall of the graveyard, though now so overgrown that it can easily be overlooked, is a corpse house, or mort safe. This was built in the early 1830s at a time when the threat from body-snatchers was at its height and is one of a number of contemporaneous corpse houses that stand in graveyards in this part of County Antrim. It was built following a meeting that was held in the graveyard on 29 January 1831. Those gathered had some claim to burial rights here. Among the rules drafted was that any body placed in the corpse house should be removed at the end of six weeks; a body not removed by the family by then would be removed after seven weeks and the family would forfeit any future right to the use of the building.

Standing a short distance to the east of the Stephenson mausoleum is a headstone commemorating the well-known local writer Florence Mary McDowell. Born in Doagh in 1888, she was daughter of William Lenox Dugan, who was originally from Castlerock in County Londonderry, and his wife Mary Jane, nee Kidley. Her childhood home was Bridge House just north of the village. In 1903 she began a long teaching career as a monitor in Cogry Mills National School. In her later years she wrote two books, Other days around me and Roses and rainbows, which vividly recaptured everyday life in late Victorian and Edwardian Doagh. She died on 11 March 1976 aged 87.

Ballylinney graveyard

The old burying ground at Ballylinney is reached by a lane that runs from the Ballylinney Road past the Ballylinney Presbyterian meeting house. Prior to the Reformation this was the site of a medieval parish church. Like Kilbride, Ballylinney has its own mort-safe or corpse house. This is well-built with a barrel vault and stone roof. Two of the more interesting figures buried here have no memorials, the entrepreneur John Rowan of Doagh, who did in 1858, and the poet Thomas Beggs, who died in 1847. Unlike most old graveyards, Ballylinney is not cared for by a local authority, but is maintained by a committee representing the families of those who hold burial rights here.

37 Ordnance Survey Memoirs, vol. 29, p. 92.

38 This section is mainly based on the publication Kilbride Presbyterian Church 1848-1998 (1998).

39 Ordnance Survey Memoirs, vol. 29, p. 141.

40 Ordnance Survey Memoirs, vol. 29, p. 135.

41 Cox, History of the Parish of Kilbride, pp 15-16.

42 Ordnance Survey Memoirs, vol. 29, p. 79.

43 PRONI, D300/1/5/48.

44 Belfast Newsletter, 4 March 1898.

45 The Rushlight, no. 3, vol. 1 (17 Dec. 1824), p. 23.