Due to the loss of nineteenth-century census returns, the 1901 census provides the first opportunity to take a detailed look at the inhabitants of Doagh and how they earned a living.

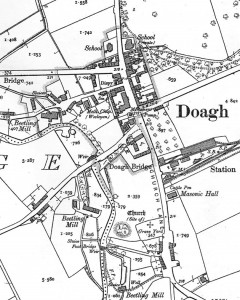

The census distinguished between ‘Doagh Town’ (i.e. the village), ‘Doagh Mill’, and the remainder, or rural portions, of the townland of Doagh. There were 225 inhabitants of Doagh Town, 152 of Doagh Mill, and 239 in the rest of the townland.

The population of Doagh was overwhelmingly Presbyterian, with smaller numbers of Anglicans, Methodists and Roman Catholics. Not surprisingly, the people of working age in ‘Doagh Mill’ were mainly employed in the mill. In ‘Doagh Town’ there were also numerous mill employees as well as a range of other trades and occupations.

A selection of these is listed below:

1. John Hill, shoemaker

6. Harry H. Morton, posting establishment

7. Eliza Milliken, grocer

8. Francis Owens, tailor

9. Robert B. Robson, National School teacher

12. Jane Ingram, postmistress

14. William Ed. Hunter, druggist

15. Martha Fleming, dressmaker

19. William Caldwell Heron, publican

20. Lizzie Bodkin, milliner

21. James Gilmore, bootmaker

23. Andrew Hunter, flesher

25. Samuel Heron, saddle master

27. John Boyd, beetler finisher of cottons and linens

29. David Grimason, tailor

49. James Greer, pig dealer

51. Samuel McConnell, wine and spirit merchant and farmer

52. Hugh Lorimer, bootmaker

59. John Frew, engine driver

62. Robert Robinson, railway engine driver

From the above list it is clear that the village was providing a number of important services to the local community. The mention of a railway engine driver is a reminder that by 1901 the village of Doagh had its own rail link. (There was another station on the LMS line from Belfast to Ballymena, but it was several miles away at Ballypalady; a horse and trap transferred travellers to Doagh.)

This extension of the Larne to Ballyclare narrow gauge line had been opened in 1884. It was reported that the cost of the Doagh extension, taking into consideration the purchase of land, legal expenses and engineering, came to £3,921, with the station another £1,473. In all, the total cost was the equivalent of £3,827 per mile.57 The Doagh extension had a fairly short history, closing in 1933.

Most people living in Doagh at the beginning of the twentieth century had been born in County Antrim, and in Doagh itself or its neighbourhood. There were some who, according to the 1901 census, had been born further afield, either in another part of Ireland or across the water in Britain. Seventeen-year-old William S. Wright had even been born in Pittsburgh in the United States. However, for sheer distance from her place of birth no-one could match 16-year-old Annie Charman, who had been born in India.

She was resident in house no. 22 in the village of Doagh, along with her father Jonathan, a 43-year-old retired schoolmaster, who had been born in Windlesham, Surrey, England, her 13-year-old brother Alexander A., who had been born in Jersey. Also present was Jonathan Charman’s 40-year-old wife, Martha, a native of Kilkenny. She was his second wife and not the mother of his children.

At the commencement of the 1900s the master of Doagh National School was R. B. Robson. He was originally from near Greyabbey, and in 1882 had spent six weeks as a substitute teacher at this school.58 Three years later Robson returned to take up a permanent position at Doagh. During Robson’s tenure the number of boys attending the school increased to the point where additional accommodation was needed. A public meeting was held with the proprietor of the local spinning mill in the chair and the response was such that the sum of £75 was promised by those in attendance. The process of having a new school built proved to be, in Robson’s own words, ‘a long and tedious affair’. The schoolmaster even enlisted the support of the MP for East Antrim, Colonel McCalmont to raise the matter in the House of Commons. The new school, which was built to accommodate 130 pupils, was opened in 1909. Robson retired in 1926. A new school, standing on the site of its predecessor, was built in 1959.

There were several other schools in the Doagh area in the early twentieth century. The nearest was Cogry Mills National School which was in existence from at least as far back as 1850. By the beginning of the twentieth century, this school had its own library. According to the teacher, as reported in the Appendix to the 69th Report of the Commissioners for National Education in Ireland … 1902, ‘the general knowledge of the pupils is increased and their vocabulary is enlarged’ as a result of the library. Furthermore, the benefits of the library went beyond simply the pupils at the school to their parents as well. This school was replaced by the Cogry Mills Memorial School which was built in the aftermath of the First World War and named in memory of those men from the area who had died in that conflict. In 1937 a new school was built on the Moyra Road – Kilbride Central – which replaced the pre-existing schools at Kilbride and Cogry.

The village of Doagh continued to expand in the course of the twentieth century. In his history of Kilbride, first published in 1959, Rev. R. R. Cox made the following observations on Doagh:

During the past few years it has taken on a new look. Where once there were open fields in the normal crop rotation – potatoes, corn and grass, a new housing estate has grown. Television aerials on roof tops appear now in ever increasing numbers. The old thatched cottage with its half-door is a thing of the past. Even the village pump has passed into an honourable retirement with the installation of piped water mains.59

In the half century since Rev. Cox wrote those words, the village had witnessed even greater changes. Today Doagh has a population of around 1,200. Most of the people who live there do not work in the village and Doagh could be described as a commuter village. Despite these changes, it still retains much of its historical character, leaving the visitor in no doubt about its rich and colourful past.

57 E. M. Patterson, A History of the Narrow-gauge Railways of North-east Ireland: The Ballymena Lines (Newton Abbott, 1968), p. 70.

58 See his Autobiography of an Ulster Teacher (Belfast, 1935).

59 Cox, History of the Parish of Kilbride, p. 63.