The village of Doagh as we know it today seems to have had its beginnings in the mid 1700s. The Belfast Newsletter of 5 July 1757 carried the following advertisement:

That at Doagh there are now a parcel of houses built by William Agnew Esq. very commodious for tradesmen, with good gardens and five acres of land or three to each house …; the same to be let and to commence the first of November next, to any person of good substance and character, that can be well recommended. … If any person incline to build a house for himself, he shall be accommodated with 12 or 14 acres of land; and if the person desire said William Agnew to build said house, it shall be done of said dimensions, according to the rent agreed on.

From the above advertisement, it is clear that William Agnew had initiated a programme of urban development, building houses for tradesmen with a portion of land attached to each – on the basis that even a skilled craftsman needed some ground to grow vegetables or keep some livestock. Agnew was also willing to be flexible and allow potential tenants to build their own houses or else have a house built to their specified dimensions.

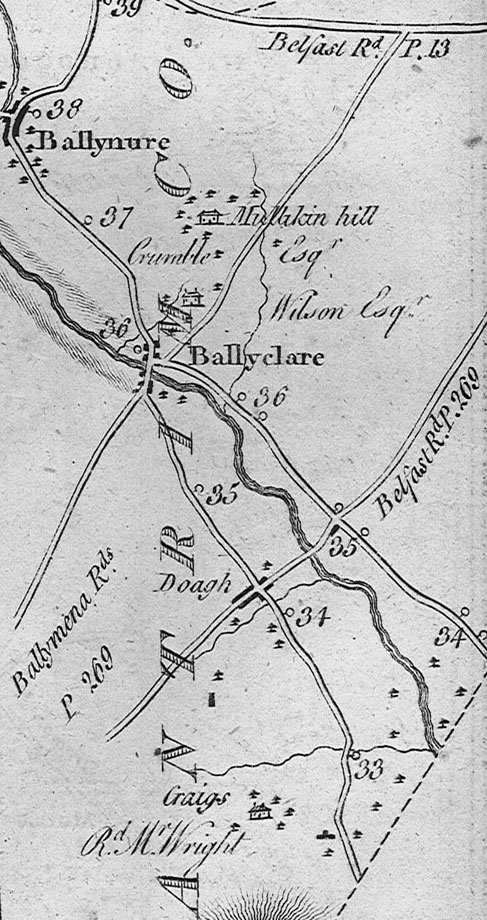

William Agnew Esq. was from Kilwaughter near Larne and at some point had acquired a lease of Doagh and Ballyhamage from the Donegall family. Agnew obviously saw in Doagh a suitable location to develop a village community. Its situation made it a prime site to do this, located as it was where the road from Belfast to Ballymena intersected the road from Larne to Antrim. Agnew was also keen to establish an inn here which he eventually did.

The road network around Doagh from Taylor and Skinner, Maps of the Roads of Ireland (1778) (click to enlarge)

Doagh continued to grow in the years after this, if not spectacularly, then steadily. A map from the collection of the Marquess of Donegall shows Doagh in 1767-70.5 The street plan of the village has not changed greatly since then. The bleach green and graveyard are marked and also an area known as ‘Milking Hill’.

The expansion of retail opportunities in Doagh is reflected in the following advertisement that appeared in the autumn of 1791: ‘Robert and James Kirkwood respectfully inform their friends and the publick that they have opened a shop in Doagh: where they are assorted with the greatest variety of goods’.6

The goods in question ranged from tea, sugar and cloth to Jamaica rum, brandy, gin and ‘strong Dublin whiskey’. The Kirkwoods indicated that they were determined to sell their wares at prices as low as the longest established shops in the district. Tea, long the preserve of the wealthy, was by this time an important part of the Irish diet. The same could be said of sugar.

While on a tour round Ireland, Daniel Beaufort stopped briefly in Doagh in November 1787 and noted in his journal:

At Doagh which is 10 miles from Randalstown, Carrickfergus, Belfast and Ballymena and 11 from Larne – I was not delayed a quarter of an hour but got on with a fine stout pair of white horses. This little inn has a neat parlour, and the landlord, Will Harpur, is active, attentive and civil.7

In February 1791 the deaths of an elderly couple in Doagh excited much more than just local interest. Between them Robert Andrew and his wife Elizabeth, whose deaths occurred just over a week apart, totalled 209 years. It was reported that they ‘enjoyed a remarkable degree of health during their whole life time; and she was able to spin to within three days of her death’.8

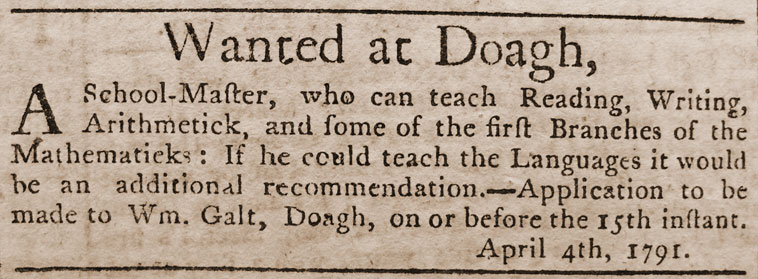

William Galt and the Doagh book club and Sunday school

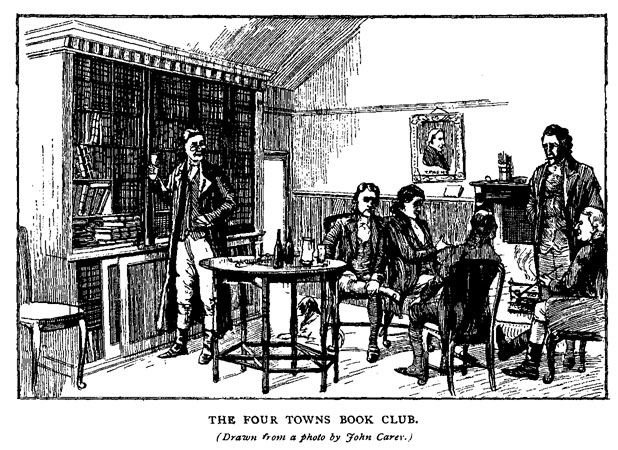

Whilst still a young man William Galt, who was then the schoolmaster of the village was inspired with the notion of forming a book club and was supported in this endeavour by like-minded, enthusiastic men. In 1768 the Reading Society was established and had thirty members. Their objective appears to have been to promote the mutual attainment of knowledge.

They purchased and read books covering a wide range of subjects, e.g. literature, science, history, mechanics, divinity etc. They also acquired a pair of 18-inch globes. Together as a Society the members had the opportunity to acquire what would have been beyond their reach as individuals. The desire for knowledge spread throughout the countryside and several reading societies similar to that in Doagh were formed in Ballyclare, Ballynure, Roughfort and Parkgate.

Illustration of the Four Towns Book Club, from Ulster Journal of Archaeology, vol. VIII (1902), p. 119 (click to enlarge)

Shortly after the Doagh Book Club was opened William Galt began to instruct the youth of the village and surrounding district. The subjects taught were reading, writing and arithmetic. Sunday proved to be the most suitable day, so that was the day set aside for this enterprise. According to the inscription on Galt’s gravestone in Kilbride Cemetery, ‘He was the first to establish a Sunday School in Ireland which he did in Doagh in 1770.’9

The Sunday School flourished and soon the number of scholars receiving tuition increased to two hundred. The Reading Society provided the books required and the teachers gave their services free of charge. It is not known where the Sunday School was originally held. It is indeed probable that neither the library nor the Sunday School had any permanent home until 1780.

In that year the members of the library applied to Edward Jones Agnew of Kilwaughter for a site on which to build a schoolhouse. This was agreed and the members raised the funds required to erect a 2-storey building containing school accommodation and also a large room in which to house their library and hold meetings. School accommodation was on the ground floor and the external stairs to the right led up to the library/assembly room. This building still stands beside the Methodist Church and is now known as the Doagh Community Hall, previously the Orange Hall. It was enlarged and renovated in 1958 and again in 2011.

Revolutionary Doagh

Towards the end of the eighteenth century the Presbyterian population of Ulster became increasingly politicised and drawn into radical politics. Doagh was one of the areas where this was especially apparent. There were various reasons for this. In the late 1770s, when the regular army was in America fighting the colonists, a part-time military force was raised in Ireland to guard the island against possible invasion.

This force became known as the Volunteers and was mainly middle class in its rank and file membership, though often with officers from the gentry and aristocracy. A company was founded in Doagh that took part in reviews, or demonstrations, that became gradually more political as Volunteers called for parliamentary reform.

On 1 July 1790 a ‘very great number of people’ gathered at Doagh to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne.10 A bonfire was lit and afterwards a number of the leading inhabitants of the area adjourned to the book club. Chairing this gathering was William Harper, the proprietor of the inn in Doagh, and a remarkable number of toasts were drunk that indicated clearly where the political sympathies of those assembled lay. These included the Glorious Revolution of 1688, freedom of the press, annual parliaments and an equal representation of the people, the Volunteers, ‘President Washington and the Free States of America’, and the French National Assembly.11

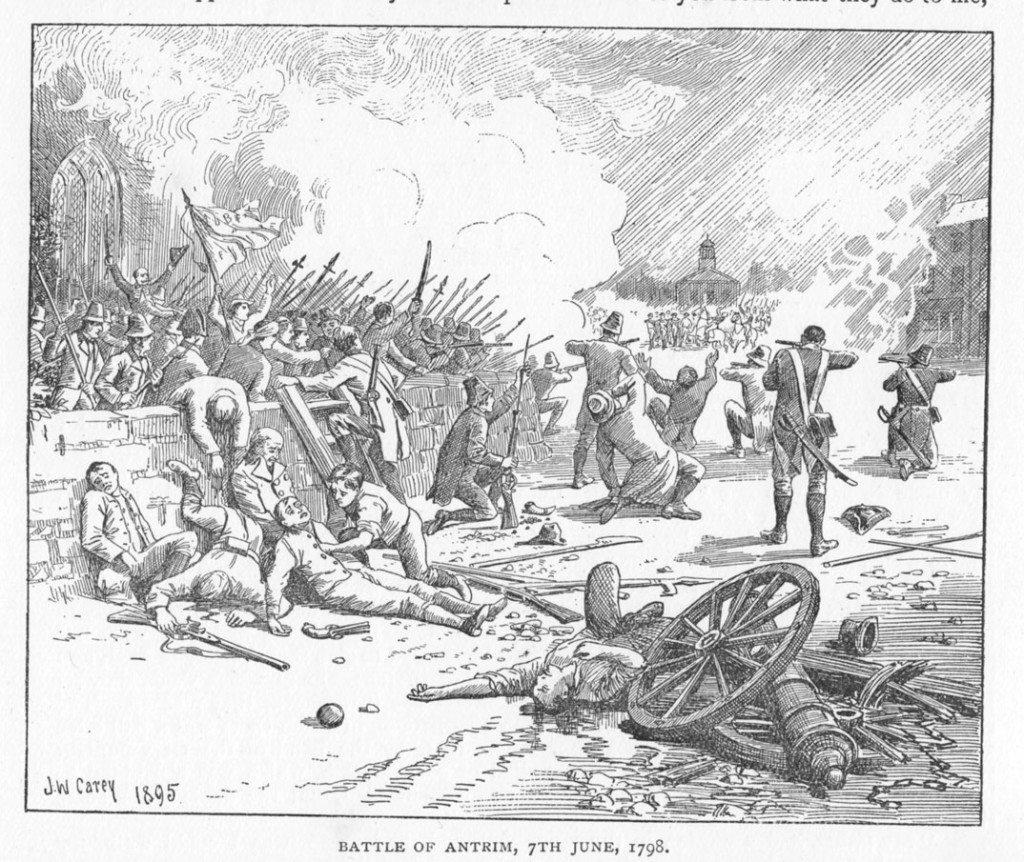

The Battle of Antrim, 1798. From Historical Notices of Old Belfast (1896), p. 194 (click to enlarge)

Influenced by the American and French Revolutions, some began to consider more radical solutions to what they believed were Ireland’s problems. The Society of United Irishmen was founded in Belfast in October 1791. Soon afterwards clubs were founded in Dublin and at a number of other places. The aims of the Society were parliamentary reform and the elimination of English interference in Irish matters.

On 27 November 1792 the Sixmilewater Society of United Irishmen met at Doagh with William Gilliland Owens of Holestone in the chair and William Galt as secretary, and passed a series of resolutions. These included a declaration that no nation could be considered free where ‘ninety-nine out of every hundred of the people are excluded from all control over the legislature’ and a call to extend the ‘rights of suffrage to the great body of the people’. Those gathered also asserted that ‘the claims of our Roman Catholick brethren perfectly modest’ and wished them success in seeking redress for their grievances. Finally, the United Irishmen of the Sixmilewater valley declared their wholehearted support for the French Revolution.

By this time enthusiasm for Volunteering was beginning to wane and in the early part of 1793 the government took action to suppress the Volunteer movement. This of course was not to everyone’s satisfaction. One final attempt to hold a Volunteer demonstration was planned for 14 September 1793 at a spot on the northern bank of the Sixmilewater near Doagh. The morning of the demonstration was cold, wet and windy, but this did not deter Volunteer companies from setting out for Doagh. However, news of the planned demonstration was by now common knowledge and the 38th Regiment, the Fermanagh Militia, and a detachment of artillery with two pieces of cannon, were sent to Doagh from Belfast to prevent any assembly of Volunteers from taking place.

Following government efforts to suppress it, the United Irish Society reorganised itself as a secret organisation and began to prepare for rebellion. There continued to be a great deal of sympathy for the United Irishmen in the Sixmilewater valley. Others thought that immense pressure was being placed on the inhabitants of the Sixmilewater valley to support the United Irish movement. Captain Andrew Macnevin in Carrickfergus reported that the people of Doagh, Ballynure and Ballyclare risked having their homes burned down if they did not support the United Irishmen.

Anyone suspected of being a United Irishman was arrested and liable to prosecution. In September 1796 John Alexander (also known as McCalshander) of Doagh was imprisoned in the county gaol and charged with high treason.12 Alexander, who was a leading figure in the Sunday school and book club in Doagh, was a shoemaker. There was a huge groundswell of sympathy for Alexander and in November of that year over 1,000 people assembled at Doagh to dig his crop of potatoes, and afterwards dug the potatoes of the mother of his apprentice who was trying to keep the shoemaking business going during Alexander’s incarceration. The following year Alexander was released without standing trial. Alexander was more fortunate than William Orr, a farmer and United Irishman from Farranshane, who was executed in Carrickfergus in October 1797. His body would have passed by Doagh on its way from Carrickfergus to Templepatrick for burial.

Rebellion began in Leinster in late May 1798. On the night of 6-7 June it spread to Ulster. Many men from the Sixmilewater Valley took part in the Battle of Antrim on 7 June. However, the rising in the north lasted barely a week. There followed a series of executions; one of the last to be hanged was the most famous Ulster rebel of them all, Henry Joy McCracken, on 17 June. Doagh was one of a number of towns and villages that ‘suffered severely by the late disturbances, both by fire and sword’.13 Memories of this were still fresh when James Boyle of the Ordnance Survey compiled his memoir in 1839: ‘In 1798 a portion of the village was burned by the king’s troops, in consequence of the part which its inhabitants took in the insurrection of that year.’14

One of the greatest acts of cultural vandalism in Ulster’s history occurred at this time when the Doagh book club was ransacked by the Carrickfergus Fencibles and its 1,500 volumes destroyed. It was probably targeted because of Galt’s known involvement with the United Irishmen. Samuel McSkimin, the author of the well-known history of Carrickfergus, was among the soldiers present in Doagh on that day and shortly before his death in 1843 spoke of his deep sense of shame at what he had witnessed:

I was one of a company of the Carrickfergus Fencibles, who received orders to visit Doagh for the double purpose of searching for arms and arresting proscribed rebels. We entered the village, but not finding the objects sought for, those in command of the party ordered the doors of the clubroom to be burst open; and the work of demolition at once commenced. The windows and entire furniture of the house were broken in pieces; a pair of elegant new globes smashed to atoms; the library shutters, enclosing the books and papers, beaten in with the musket ends; and the books thrown into the street, forming a huge pile, were set fire to and burned.15

McSkimin himself tried to salvage a copy of Robertson’s History of Charles the Fifth, but a fellow soldier snatched it away from him and kicked it into the fire. ‘Never, either before or since, did I return home with a heavier heart’, recalled McSkimin, his regret compounded by the fact that it was here that he had received ‘the first rudiments of education’. The book club was revived after the rebellion and continued to exist until the middle of the nineteenth century.

5 PRONI, D835/1/3/27.

6 Belfast Newsletter, 28 Oct.-1 Nov. 1791.

7 PRONI, MIC250/1.

8 Belfast Newsletter, 4-8 March 1791.

9 See Cox, History of the Parish of Kilbride, pp 53-4 for the debate over whether or not the Sunday school in Doagh was the earliest in Ireland; see also W. S. Smith, Doagh and the ‘first’ Sunday school in Ireland (Belfast, 1890).

10 It is interesting that they were still using 1 July as the anniversary. This was the date of the battle, but after the calendar was changed in 1752 the anniversary fell on 12 July.

11 Belfast Newsletter, 9-13 July 1790.

12 Belfast Newsletter, 26-30 Sept. 1796.

13 Belfast Newsletter, 12 June 1798.

14 Ordnance Survey Memoirs, vol. 29, p. 68.

15 Northern Whig, 17 April 1874.